Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6950 results in Algorithmics, Complexity, Computer Algebra, Computational Geometry

References

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 210-215

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

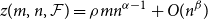

14 - Weighted Graphs

- from Part III - Modeling Complex Networks

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 197-209

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

- from Part I - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 3-7

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Connectivity

- from Part II - Erdős–Rényi–Gilbert Model

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 78-84

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Large Subgraphs

- from Part II - Erdős–Rényi–Gilbert Model

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 93-110

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 1-2

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

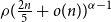

4 - Evolution

- from Part II - Erdős–Rényi–Gilbert Model

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 45-63

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Small World

- from Part III - Modeling Complex Networks

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 154-162

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Extreme Characteristics

- from Part II - Erdős–Rényi–Gilbert Model

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 111-124

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp ix-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Random Graphs and Networks: A First Course

-

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023

Poset Ramsey numbers: large Boolean lattice versus a fixed poset

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 4 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 February 2023, pp. 638-653

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

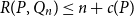

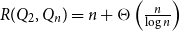

Multiple random walks on graphs: mixing few to cover many

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 4 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 February 2023, pp. 594-637

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Random feedback shift registers and the limit distribution for largest cycle lengths

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 4 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 February 2023, pp. 559-593

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Bipartite-ness under smooth conditions

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 4 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 February 2023, pp. 546-558

-

- Article

- Export citation

Convergence of blanket times for sequences of random walks on critical random graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 3 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2023, pp. 478-515

-

- Article

- Export citation

Off-diagonal book Ramsey numbers

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 3 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2023, pp. 516-545

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

-

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022

-

- Textbook

- Export citation