Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6974 results in Algorithmics, Complexity, Computer Algebra, Computational Geometry

6 - Topological Analysis of Point Clouds

-

- Book:

- Computational Topology for Data Analysis

- Published online:

- 18 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2022, pp 178-206

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Computational Topology for Data Analysis

- Published online:

- 18 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2022, pp v-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Computational Topology for Data Analysis

- Published online:

- 18 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2022, pp 429-434

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Topological Persistence and Machine Learning

-

- Book:

- Computational Topology for Data Analysis

- Published online:

- 18 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2022, pp 389-410

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Generators and Optimality

-

- Book:

- Computational Topology for Data Analysis

- Published online:

- 18 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2022, pp 148-177

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Computational Topology for Data Analysis

- Published online:

- 18 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2022, pp 411-428

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

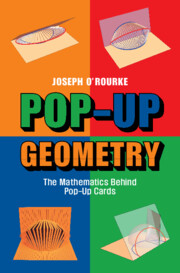

Pop-Up Geometry

- The Mathematics Behind Pop-Up Cards

-

- Published online:

- 03 March 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 March 2022

Refined universality for critical KCM: lower bounds

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 5 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 March 2022, pp. 879-906

-

- Article

- Export citation

Computational Topology for Data Analysis

-

- Published online:

- 18 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2022

Unusually large components in near-critical Erdős–Rényi graphs via ballot theorems

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 5 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2022, pp. 840-869

-

- Article

- Export citation

Short proofs for long induced paths

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 5 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 February 2022, pp. 870-878

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Theoretical Computer Science for the Working Category Theorist

-

- Published online:

- 25 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 03 March 2022

-

- Element

- Export citation

Removal lemmas and approximate homomorphisms

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 4 / July 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 January 2022, pp. 721-736

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

12 - Parameter table

-

- Book:

- Strongly Regular Graphs

- Published online:

- 06 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 January 2022, pp 399-424

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Strongly Regular Graphs

- Published online:

- 06 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 January 2022, pp xv-xviii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Buildings

-

- Book:

- Strongly Regular Graphs

- Published online:

- 06 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 January 2022, pp 114-138

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Cyclotomic constructions

-

- Book:

- Strongly Regular Graphs

- Published online:

- 06 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 January 2022, pp 174-196

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Parameter Index

-

- Book:

- Strongly Regular Graphs

- Published online:

- 06 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 January 2022, pp 451-452

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Combinatorial constructions

-

- Book:

- Strongly Regular Graphs

- Published online:

- 06 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 January 2022, pp 197-248

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Strongly Regular Graphs

- Published online:

- 06 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 13 January 2022, pp v-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation