Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6974 results in Algorithmics, Complexity, Computer Algebra, Computational Geometry

Mathematics for Future Computing and Communications

-

- Published online:

- 03 December 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 December 2021

The Shortest Path to Network Geometry

- A Practical Guide to Basic Models and Applications

-

- Published online:

- 02 December 2021

- Print publication:

- 06 January 2022

-

- Element

- Export citation

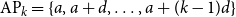

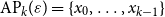

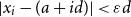

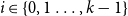

A blurred view of Van der Waerden type theorems

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 4 / July 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 26 November 2021, pp. 684-701

-

- Article

- Export citation

Higher-Order Networks

-

- Published online:

- 23 November 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 December 2021

-

- Element

- Export citation

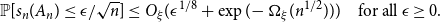

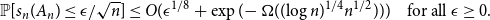

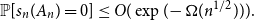

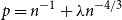

On the smallest singular value of symmetric random matrices

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 4 / July 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 November 2021, pp. 662-683

-

- Article

- Export citation

Extending the Tutte and Bollobás–Riordan polynomials to rank 3 weakly coloured stranded graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 3 / May 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 October 2021, pp. 507-549

-

- Article

- Export citation

Game Theory Basics

-

- Published online:

- 22 October 2021

- Print publication:

- 19 August 2021

-

- Textbook

- Export citation

Asymptotics for the number of standard tableaux of skew shape and for weighted lozenge tilings

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 4 / July 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 October 2021, pp. 550-573

-

- Article

- Export citation

On bucket increasing trees, clustered increasing trees and increasing diamonds

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 4 / July 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 October 2021, pp. 629-661

-

- Article

- Export citation

The critical window in random digraphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 3 / May 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 October 2021, pp. 411-429

-

- Article

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notation

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp xv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Convex Optimization and Efficiency

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 49-68

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Ellipsoid Method for Convex Optimization

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 279-309

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Newton’s Method

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 160-184

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

New dualities from old: generating geometric, Petrie, and Wilson dualities and trialities of ribbon graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 4 / July 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 October 2021, pp. 574-597

-

- Article

- Export citation

6 - Gradient Descent

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 84-107

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Preliminaries

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 17-34

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Algorithms for Convex Optimization

- Published online:

- 24 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2021, pp 310-318

-

- Chapter

- Export citation