Refine listing

Actions for selected content:

1417513 results in Open Access

Customized Spectral Libraries for Effective Mineral Exploration: Mining National Mineral Collections

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 66 / Issue 3 / June 2018

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 297-314

-

- Article

- Export citation

In situ X-ray Diffraction Study of the Swelling of Montmorillonite as Affected by Exchangeable Cations and Temperature

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 59 / Issue 2 / April 2011

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 165-175

-

- Article

- Export citation

Influence of Mechanical Compaction and Clay Mineral Diagenesis on the Microfabric and Pore-Scale Properties of Deep-Water Gulf of Mexico Mudstones

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 54 / Issue 4 / August 2006

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 500-514

-

- Article

- Export citation

Benzene Vapor Sorption by Organobentonites From Ambient Air

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 50 / Issue 4 / August 2002

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 421-427

-

- Article

- Export citation

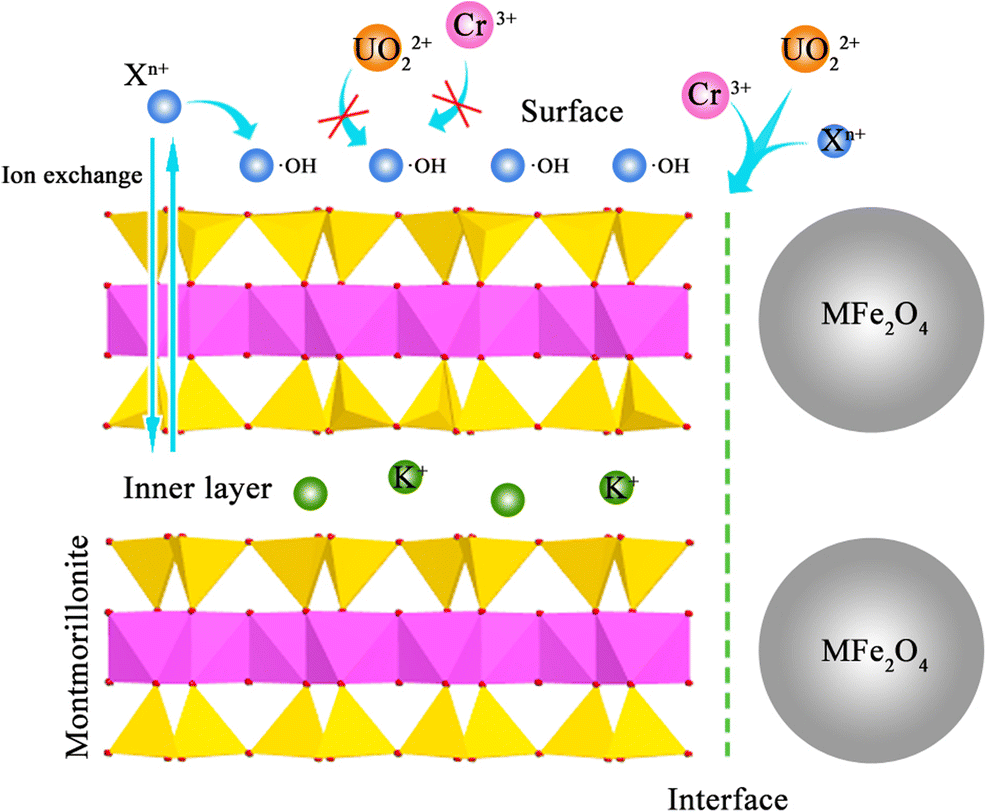

Competitive Adsorption of Uranyl and Toxic Trace Metal Ions at MFe2O4-montmorillonite (M = Mn, Fe, Zn, Co, or Ni) Interfaces

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 67 / Issue 4 / August 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 291-305

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Role of the Clergy in the Establishment and Consolidation of Pahlavi I (1925–1941)

-

- Journal:

- Iranian Studies / Volume 57 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 January 2024, pp. 143-163

- Print publication:

- January 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Boron and Lithium Isotopic Signatures of Nanometer-Sized Smectite-Rich Mixed-Layers of Bentonite Beds From Campos Basin (Brazil)

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 70 / Issue 1 / February 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 72-83

-

- Article

- Export citation

A Molality-Based BET Equation for Modeling the Activity of Water Sorbed on Clay Minerals

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 60 / Issue 6 / December 2012

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 599-609

-

- Article

- Export citation

A critical examination of safety culture in the superyacht industry

-

- Journal:

- The Journal of Navigation / Volume 77 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 September 2024, pp. 100-115

- Print publication:

- January 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Arsenic Sorption onto Soils Enriched in Mn and Fe Minerals

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 51 / Issue 2 / April 2003

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 197-204

-

- Article

- Export citation

Significance of phyllosilicate mineralogy and mineral chemistry in an epithermal environment. Insights from the palai-islica Au-Cu deposit (Almería, SE Spain)

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 57 / Issue 1 / February 2009

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 1-24

-

- Article

- Export citation

Forthcoming Papers

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 52 / Issue 1 / February 2004

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, p. 141

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

An Endless Capacity for Dissembling: Representing Teenage Girls on the American Stage from The Children's Hour through If Pretty Hurts Ugly Must Be a Muhfucka

-

- Journal:

- Theatre Survey / Volume 65 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 March 2024, pp. 37-59

- Print publication:

- January 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Sharing of the Profits of the Carrera de Indias: The Actors of the Hispanic Colonial Trade and Their Monopolistic Practices in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century

-

- Journal:

- The Americas / Volume 81 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2024, pp. 39-66

- Print publication:

- January 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

ARTWORK: ED COOPER

-

- Article

- Export citation

Sorption and Direct Electrochemistry of Mitochondrial Cytochrome C on Hematite Surfaces

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 53 / Issue 6 / December 2005

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 564-571

-

- Article

- Export citation

Powder X-Ray Diffraction Study of the Hydration and Leaching Behavior of Nontronite

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 59 / Issue 6 / December 2011

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 560-567

-

- Article

- Export citation

Origin of Saponite-Rich Clays in A Fossil Serpentinite-Hosted Hydrothermal System in The Crustal Basement of The Hyblean Plateau (Sicily, Italy)

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 60 / Issue 1 / February 2012

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 18-31

-

- Article

- Export citation

Measurement of clay surface areas by polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) sorption and its use for quantifying illite and smectite abundance

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 52 / Issue 5 / October 2004

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 589-602

-

- Article

- Export citation

AJL volume 14 issue 1 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Asian Journal of International Law / Volume 14 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 January 2024, pp. f1-f7

- Print publication:

- January 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation