Refine search

Actions for selected content:

90438 results in Archaeology

PPR volume 90 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 90 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 March 2025, pp. f1-f5

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Recycling and repair on the Roman frontier: a hoard of mail armour from Bonn

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Parcours dans l'espace domestique romain à travers deux approches problématiques contrastées

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Roman Archaeology / Volume 37 / Issue 2 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 January 2025, pp. 644-655

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Cache Complexes in Tikal, Petén, Guatemala (800 BC–AD 950)

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity / Volume 35 / Issue 4 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2025, pp. 870-888

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

JRO volume 37 issue 2 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Roman Archaeology / Volume 37 / Issue 2 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 March 2025, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

LAQ volume 35 issue 4 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity / Volume 35 / Issue 4 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2025, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Time and Change in Mesolithic Britain c. 9800–3600 cal bc

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 90 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 February 2025, pp. 319-352

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Bronze Age Fields in Suffolk: a Preliminary Survey

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 90 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 December 2024, pp. 279-318

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

RDC volume 66 issue 6 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 6 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 January 2025, pp. b1-b2

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

THE THIRD MILLENNIUM B.C.E. POTTERY SEQUENCE OF SOUTHERN MESOPOTAMIA: POTTERY CHRONOLOGY AS SEEN FROM TELL ZURGHUL/NIGIN, MOUND A

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

From proof and unproof to critical fabulation: a response to Frieman

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

RDC volume 66 issue 6 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 6 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 January 2025, pp. f1-f6

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Do cultural and biological variation correspond in the Middle Nile Valley Neolithic? Some insights from dental morphology

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Heritage Conflict and the Council: The UNSC, UNESCO, and the View from Iraq and Syria

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Cultural Property / Volume 31 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 November 2024, pp. 134-153

-

- Article

- Export citation

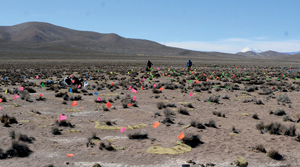

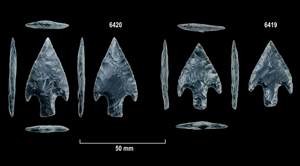

Paiján obsidian points on the coastal desert of southern Peru and their source

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Ancient Maya Economies

-

- Published online:

- 26 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024

-

- Element

- Export citation

Heritage and Transformation of an African Popular Music

-

- Published online:

- 26 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2024

-

- Element

- Export citation

Sailing to Calanais: Monument Complexes and the Sea in the Neolithic of Western Scotland and Beyond

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society / Volume 90 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 November 2024, pp. 253-277

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Merovingian Worlds

-

- Published online:

- 22 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024