Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6950 results in Algorithmics, Complexity, Computer Algebra, Computational Geometry

6 - Analysis of Algorithms

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 267-326

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 661-666

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Logic

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 79-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Looking Forward

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 657-660

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Graphs and Trees

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 577-656

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 667-676

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp xiii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Credits

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp xv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Mathematical Induction

-

- Book:

- Connecting Discrete Mathematics and Computer Science

- Published online:

- 16 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 215-266

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

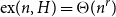

A BK inequality for random matchings

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 1 / January 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 July 2022, pp. 151-157

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

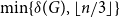

Many Turán exponents via subdivisions

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 1 / January 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 July 2022, pp. 134-150

-

- Article

- Export citation

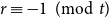

Clustered colouring of graph classes with bounded treedepth or pathwidth

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 1 / January 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 July 2022, pp. 122-133

-

- Article

- Export citation

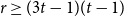

Triangles in randomly perturbed graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 1 / January 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 July 2022, pp. 91-121

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Percolation in Spatial Networks

- Spatial Network Models Beyond Nearest Neighbours Structures

-

- Published online:

- 15 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 14 July 2022

-

- Element

- Export citation

Complete subgraphs in a multipartite graph

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 6 / November 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 June 2022, pp. 1092-1101

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Hypergraphs without non-trivial intersecting subgraphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 6 / November 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 June 2022, pp. 1076-1091

-

- Article

- Export citation

On the peel number and the leaf-height of Galton–Watson trees

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 1 / January 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 June 2022, pp. 68-90

-

- Article

- Export citation

Colouring graphs with forbidden bipartite subgraphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 1 / January 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 June 2022, pp. 45-67

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Sandwiching biregular random graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 1 / January 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 June 2022, pp. 1-44

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Community detection and percolation of information in a geometric setting

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 31 / Issue 6 / November 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 May 2022, pp. 1048-1069

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation