Refine search

Actions for selected content:

90474 results in Archaeology

AAQ volume 89 issue 2 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- American Antiquity / Volume 89 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 May 2024, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Fiber Artifacts from the Paisley Caves: 14,000 Years of Plant Selection in the Northern Great Basin

-

- Journal:

- American Antiquity / Volume 89 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 April 2024, pp. 238-262

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

RDC volume 66 issue 2 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 May 2024, pp. b1-b2

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Thematic Analysis of Indigenous Perspectives on Archaeology and Cultural Resource Management Industries

-

- Journal:

- American Antiquity / Volume 89 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 April 2024, pp. 185-201

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Early Beringian Traditions: Functioning and Economy of the Stone Toolkit from Swan Point CZ4b, Alaska

-

- Journal:

- American Antiquity / Volume 89 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 April 2024, pp. 279-301

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

AAQ volume 89 issue 2 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- American Antiquity / Volume 89 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 May 2024, pp. b1-b2

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

EARLY HOLOCENE OXYGEN ISOTOPE CHRONOLOGIES (11,267–6420 CAL BP) FROM ICE WEDGE AT CHARA, TRANSBAIKALIA

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 April 2024, pp. 400-409

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

RDC volume 66 issue 2 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 May 2024, pp. f1-f4

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Estimation of Groundwater Residence Time Using Radiocarbon and Stable Isotope Ratio in Dissolved Inorganic Carbon and Soil CO2

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 April 2024, pp. 249-266

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

AQY volume 98 issue 398 Cover and Back matter

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Nutritional deficiency and ecological stress in the Middle to Final western Jōmon

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Editor's Corner

-

- Journal:

- American Antiquity / Volume 89 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 May 2024, pp. 163-164

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

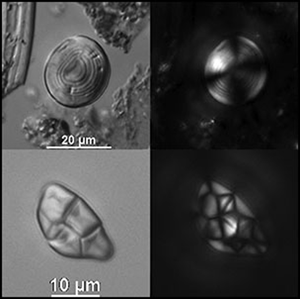

Reconstructing Late Neolithic animal management practices at Kangjia, North China, using microfossil analysis of dental calculus

- Part of

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

ADDRESSING THE INTENSITY OF CHANGES IN THE PREHISTORIC POPULATION DYNAMICS: POPULATION GROWTH RATE ESTIMATIONS IN THE CENTRAL BALKANS EARLY NEOLITHIC

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 66 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 April 2024, pp. 280-294

- Print publication:

- April 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

AQY volume 98 issue 398 Cover and Front matter

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Understanding and calculating household size, wealth, and inequality in the Maya Lowlands

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 34 / Issue 3 / Fall 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 March 2024, e1

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

EAA volume 27 issue 1 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- European Journal of Archaeology / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / February 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 March 2024, pp. b1-b2

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Inequality, urbanism, and governance at Coba and the Northern Maya Lowlands

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 34 / Issue 3 / Fall 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 March 2024, e3

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

EAA volume 27 issue 1 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- European Journal of Archaeology / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / February 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 March 2024, pp. f1-f3

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation