Refine search

Actions for selected content:

25823 results in Abstract analysis

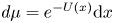

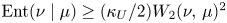

Transportation on spheres via an entropy formula

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section A: Mathematics / Volume 153 / Issue 5 / October 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 September 2022, pp. 1467-1478

- Print publication:

- October 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

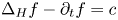

A note on monotonicity and Bochner formulas in Carnot groups

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section A: Mathematics / Volume 153 / Issue 5 / October 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 September 2022, pp. 1543-1563

- Print publication:

- October 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

VARIANTS OF A MULTIPLIER THEOREM OF KISLYAKOV

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Institute of Mathematics of Jussieu / Volume 23 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 September 2022, pp. 347-377

- Print publication:

- January 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

JMJ volume 21 issue 5 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Institute of Mathematics of Jussieu / Volume 21 / Issue 5 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 September 2022, pp. b1-b2

- Print publication:

- September 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

JMJ volume 21 issue 5 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Institute of Mathematics of Jussieu / Volume 21 / Issue 5 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 September 2022, pp. f1-f2

- Print publication:

- September 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

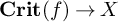

A DERIVED LAGRANGIAN FIBRATION ON THE DERIVED CRITICAL LOCUS

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the Institute of Mathematics of Jussieu / Volume 23 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 August 2022, pp. 311-345

- Print publication:

- January 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Truncated versions of three identities of Euler and Gauss

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society / Volume 65 / Issue 3 / August 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 30 August 2022, pp. 775-798

-

- Article

- Export citation

Part I - Elements of Probability Theory

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 1-2

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

21 - Regression Analysis

- from Part III - Elements of Statistical Inference

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 329-355

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Distributions on the Real Line

- from Part I - Elements of Probability Theory

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 34-40

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Multivariate Distributions

- from Part I - Elements of Probability Theory

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 68-77

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Multiple Numerical Samples

- from Part III - Elements of Statistical Inference

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 271-288

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Sampling and Simulation

- from Part II - Practical Considerations

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 127-137

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Expectation and Concentration

- from Part I - Elements of Probability Theory

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 78-99

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Practical Considerations

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 125-126

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp ix-xiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Convergence of Random Variables

- from Part I - Elements of Probability Theory

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 100-112

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Stochastic Processes

- from Part I - Elements of Probability Theory

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 113-124

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Discrete Distributions

- from Part I - Elements of Probability Theory

-

- Book:

- Principles of Statistical Analysis

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 41-53

-

- Chapter

- Export citation