Refine search

Actions for selected content:

25820 results in Abstract analysis

5 - Local Methods in the Theory of Twisted Sums

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 243-286

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Complemented Subspaces of Banach Spaces

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 9-45

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Language of Homology

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 46-127

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 521-542

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 543-548

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Back to Banach Space Theory

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 468-520

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - The Functor Ext and the Homology Sequences

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 197-242

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp i-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A homogenised model for the motion of evaporating fronts in porous media

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- European Journal of Applied Mathematics / Volume 34 / Issue 4 / August 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 January 2023, pp. 806-837

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Conjugacy growth in the higher Heisenberg groups

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Glasgow Mathematical Journal / Volume 65 / Issue S1 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 January 2023, pp. S148-S169

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Slope equality of non-hyperelliptic Eisenbud–Harris special fibrations of genus 4

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Glasgow Mathematical Journal / Volume 65 / Issue 2 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 January 2023, pp. 284-287

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Homological Methods in Banach Space Theory

-

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023

Weakly concave operators

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section A: Mathematics / Volume 154 / Issue 1 / February 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 January 2023, pp. 1-32

- Print publication:

- February 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The family signature theorem

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section A: Mathematics / Volume 154 / Issue 6 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 January 2023, pp. 2024-2067

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Battleship, tomography and quantum annealing

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- European Journal of Applied Mathematics / Volume 34 / Issue 4 / August 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 January 2023, pp. 758-773

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Connected sums of codimension two locally flat submanifolds

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section A: Mathematics / Volume 154 / Issue 6 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 January 2023, pp. 1937-1944

- Print publication:

- December 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Geometric Inverse Problems

- With Emphasis on Two Dimensions

-

- Published online:

- 15 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 January 2023

On parabolic subgroups of symplectic reflection groups

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Glasgow Mathematical Journal / Volume 65 / Issue 2 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2023, pp. 401-413

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation

Convergence of blanket times for sequences of random walks on critical random graphs

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Combinatorics, Probability and Computing / Volume 32 / Issue 3 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2023, pp. 478-515

-

- Article

- Export citation

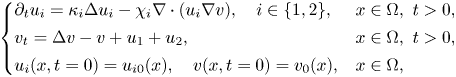

On the global existence of solutions to chemotaxis system for two populations in dimension two

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section A: Mathematics / Volume 153 / Issue 6 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2023, pp. 2106-2128

- Print publication:

- December 2023

-

- Article

- Export citation