Refine listing

Actions for selected content:

1418289 results in Open Access

INS volume 30 issue 9 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society / Volume 30 / Issue 9 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 January 2025, pp. f1-f4

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

The morphology and spectroscopy of diamonds recovered from the Prairie Creek lamproite in Arkansas, USA

-

- Journal:

- Mineralogical Magazine / Volume 89 / Issue 3 / June 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 January 2025, pp. 307-327

-

- Article

- Export citation

Oriented Temperley–Lieb algebras and combinatorial Kazhdan–Lusztig theory

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Canadian Journal of Mathematics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 1-43

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

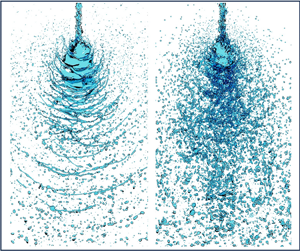

Turbulent atomisation of impinging jets under rising backpressure

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1003 / 25 January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, A15

-

- Article

- Export citation

Yellowcatite, KNaFe3+2(Se4+O3)2(V5+2O7)·7H2O, the first selenite-vanadate

-

- Journal:

- Mineralogical Magazine / Volume 89 / Issue 3 / June 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 421-427

-

- Article

- Export citation

Refining Quinean Naturalism: An Alternative to Kemp’s Stimulus Field Approach

-

- Journal:

- Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review / Revue canadienne de philosophie , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Rationality of Emotions Across Time

-

- Journal:

- Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review / Revue canadienne de philosophie , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

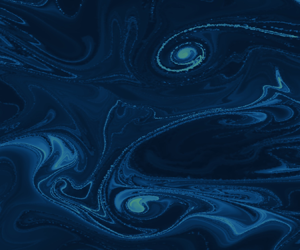

Clustering of buoyant tracer in quasi-geostrophic coherent structures

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1003 / 25 January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, A16

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Identifying genetic differences between bipolar disorder and major depression through multiple genome-wide association analyses

-

- Journal:

- The British Journal of Psychiatry / Volume 226 / Issue 2 / February 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 79-90

- Print publication:

- February 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Taiwan's Presidents: Profiles of the Majestic Six John F. Copper. London and New York: Routledge, 2024. 242 pp. £36.99 (pbk). ISBN 9781032697901

-

- Journal:

- The China Quarterly / Volume 261 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 283-284

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

- Export citation

Elliptic hyperlogarithms

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Canadian Journal of Mathematics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 1-36

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

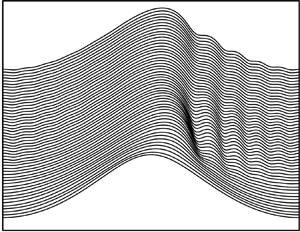

Time-dependent nonlinear gravity–capillary surface waves with viscous dissipation and wind forcing

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1003 / 25 January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, A13

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

List of Reviewers: 1 November 2023–31 October 2024

-

- Journal:

- British Journal of Nutrition / Volume 133 / Issue 1 / 14 January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 February 2025, pp. 136-144

- Print publication:

- 14 January 2025

-

- Article

- Export citation

Race, Voice, and Authority in Discussion Groups

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics / Volume 23 / Issue 3 / September 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 1013-1034

- Print publication:

- September 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

A new model for radiocarbon dating of marine shells from the Netherlands

-

- Journal:

- Radiocarbon / Volume 67 / Issue 2 / April 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 378-411

- Print publication:

- April 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The effect of different exchangeable cations on the CO2 adsorption capacity of Laponite RD®

-

- Journal:

- Clay Minerals / Volume 60 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 53-59

-

- Article

- Export citation

Reactions to no-fault compensation schemes for occupational diseases in the Netherlands: the role of perceived procedural justice, outcome concerns and trust in authorities

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Law in Context / Volume 21 / Issue 3 / September 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 367-388

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Viola Franziska Müller. Escape to the City. Fugitive Slaves in the Antebellum Urban South. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill (NC) 2022. xii, 248 pp. Ill. Maps. $99.00. (Paper: $32.95; E-book: $22.99.)

-

- Journal:

- International Review of Social History / Volume 69 / Issue 3 / December 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 502-505

-

- Article

- Export citation

Dietary preferences and collagen to collagen prey-predator trophic discrimination factors (Δ13C, Δ15N) in late Pleistocene cave hyena

-

- Journal:

- Quaternary Research / Volume 123 / January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 27-40

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

A Pleistocene hyenid trackway from the Cape south coast of South Africa

-

- Journal:

- Quaternary Research / Volume 123 / January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 January 2025, pp. 59-69

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation