Refine search

Actions for selected content:

237882 results in Physics and Astronomy

PSP volume 180 issue 2 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society / Volume 180 / Issue 2 / March 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 February 2026, pp. f1-f2

- Print publication:

- March 2026

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Improvement in High-Average-Power Laser Resistance of an Optically Addressed Spatial Light Modulator Based on a New Air-Gap Structure

-

- Journal:

- High Power Laser Science and Engineering / Accepted manuscript

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 February 2026, pp. 1-25

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

New sub-types and transition mechanisms within the canonical six shock interference patterns

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1029 / 25 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 February 2026, A1

-

- Article

- Export citation

Destabilisation of Alfvénic ion temperature gradient modes in the core plasma on HL-2A tokamak

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Plasma Physics / Volume 92 / Issue 1 / February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, E5

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Linear stability of nanofluid boundary-layer flow over a flat plate

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, A45

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Hybrid fluid–kinetic simulations of resistive instabilities in runaway electron beams

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Plasma Physics / Volume 92 / Issue 1 / February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, E3

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Tsunami and induced magnetic anomalies generated by slender fault

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, A42

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Self-regulating non-equilibrium in a slender body’s turbulent wake

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, A49

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Viscosity contrast destabilises radial Rayleigh–Taylor flow

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, R2

-

- Article

- Export citation

Investigation on the cavitation characteristics induced by high-intensity focused ultrasonic waves in a near-wall region

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, A48

-

- Article

- Export citation

Experimental measurement of the Prandtl–Meyer function in non-ideal supersonic flows

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, A41

-

- Article

- Export citation

The SAMI Galaxy Survey: Quenching of Star Formation in Clusters III. Ram-Pressure-Affected Galaxy Populations

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Accepted manuscript

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, pp. 1-26

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Population synthesis of double white dwarfs: evolutionary effects on system properties

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Accepted manuscript

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, pp. 1-10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Direct numerical simulation of the effects of a smooth surface hump on transition in swept-wing boundary layers

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, A47

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

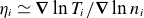

Analytic model for neutral penetration and plasma fueling

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Plasma Physics / Volume 92 / Issue 1 / February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, E4

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

New techniques to investigate the AGN-SF connection with integral field spectroscopy

-

- Journal:

- Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia / Volume 43 / 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 February 2026, e023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Many-Body Green's Functions for Time-Dependent Problems

-

- Published online:

- 06 February 2026

- Print publication:

- 05 March 2026

Direct generation of high-power femtosecond Laguerre-Gaussian and Bessel vortex beams in a thin-disk laser oscillator

-

- Journal:

- High Power Laser Science and Engineering / Accepted manuscript

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 February 2026, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

On the generation of corner flow circulation at highly rarefied conditions

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 February 2026, A44

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Undulatory hydrodynamics of tapered elastic plates in viscous fluid

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Fluid Mechanics / Volume 1028 / 10 February 2026

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 February 2026, A37

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

, with σ

, with σ